Go to

http://humanisticsystems.com/2013/09/21/human-error-the-handicap-of-human-factors-safety-and-justice/

Views on human factors and safety from the perspectives of humanistic thinking, systems thinking and design thinking.

Saturday, September 21, 2013

Safety culture cards application: Exploring experiences using Schein’s cycle

Go to:

http://humanisticsystems.com/2013/08/26/safety-culture-cards-application-exploring-experiences-using-scheins-cycle/

http://humanisticsystems.com/2013/08/26/safety-culture-cards-application-exploring-experiences-using-scheins-cycle/

Tuesday, August 27, 2013

Humanistic by Design...has moved

Hi, this blog has moved over to WordPress at http://humanisticsystems.wordpress.com

The lastest post is Safety culture cards application: Exploring experiences using Schein’s cycle

Please head on over there.

The lastest post is Safety culture cards application: Exploring experiences using Schein’s cycle

Please head on over there.

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

Tuesday, July 2, 2013

Target Culture: Lessons in Unintended Consequences

By Steven Shorrock & Tony Licu

The text in this article first appeared in HindSight 17, EUROCONTROL, July 2013.

Since we emerged from the depths of winter, many of us are still are afflicted by the ‘potholes’ that developed in the roads during the cold temperatures. These potholes are dangerous. They change drivers’ visual scanning, cause drivers to swerve, and sometimes lead to loss of control, and ultimately to several deaths. Potholes are also very expensive in terms of the damage to vehicles and costs to authorities. A 2013 survey in England and Wales by the Asphalt Industry Alliance suggested a repair bill for local councils of £113 million just to fill the holes. In an era of austerity, potholes are a real headache for local authorities. To get them fixed British councils have set numerical targets to fix each hole.

Now imagine you are part of a road maintenance team, and you have to fix each pothole in 13 minutes, within 24 hours of the hole being reported. You know from your experience and records that this is well below the time needed to properly fill a hole. But the target has been set and you and the council will be evaluated based on performance against the target. So what would you do? Maintenance teams in the UK found themselves in exactly this situation. What they did was entirely understandable, and predictable: they made temporary fixes. According to Malcolm Dawson, Assistant Director of Stoke-on-Trent City Council’s Highways Service, “Ninety nine per cent of every single job that we did was a temporary job. That meant that the staff on site who were doing the value work knew that this would fail anything between two and four weeks, but we kept sending them out as management to do as many of them as they possible could.” (see video at http://vimeo.com/58107852.)

The target was achieved, but holes reappeared and more costly rework was needed. Several councils have now dropped the numerical repair time targets, aiming instead for permanent, ‘right first time’ repairs – an approach designed with the front line staff, using a ‘systems thinking’ approach.

Targetology

|

| Numerical targets do affect behaviour and system performance. The question is, do they affect performance in the right way? Image: Paolo Camera CC BY 2.0 |

And why all this is important for you specifically, as Air Traffic Controllers – the main readers of HindSight magazine? Well, targets in ATM sooner or later affect your daily practice and we think it is important for you to have a glimpse inside the world of targets more generally.

There are several reasons why targets can seem like a good idea, but these are usually built on assumptions (see Seddon, 2003, 2008).

Targets set direction, don’t they?

One justification is that targets set direction, so people know what to do, how much, how quickly, etc. Experience shows that numerical targets do indeed set direction; they set people in the direction of meeting the numerical target, not necessarily achieving a desired system state. In her book ‘Thinking in systems’ (2008), Donella Meadows said, “If the goal is defined badly, if it doesn’t measure what it’s supposed to measure, if it doesn’t reflect the real welfare of the system, then the system can’t possibly produce a desirable result” (p. 138). She gives the example that if national security is defined in terms of the amount of money spent on the military, the system will produce military spending, and not necessarily national security. Targets can set a system in a direction that no-one actually wants.

Targets motivate people, don’t they?

Another justification is that targets motivate people to improve. This assumes that people need an external motivator to do good work (contrary to research in psychology), and ignores the fact that the vast majority of outcomes are governed by the design of the system, not the individuals in the job roles. But targets certainly do motivate people. They motivate people to do anything to be seen to achieve the target, not to achieve the purpose from the end-user’s perspective. Targets motivate the wrong sort of behaviour. And if a target is missed or unachievable, then what?

Targets allow comparison, don’t they?

In a competitive world, where cost-efficiency is under the spotlight, it is tempting to think that numerical targets provide a means of comparing the performance of different entities. It is true that targets allow comparison, but experience shows it often allows comparing false, manipulated or meaningless data.

This may seem like a cynical set of responses to three of the most common reasons for targets. But the unintended consequences of targets have been well documented in many different types of systems. This isn’t new. Economists and social scientists have known for centuries that interventions in complex systems can have unwanted effects, different to the outcome that was intended. Over 300 years ago, the English philosopher John Locke urged the defeat of a sort of target enshrined in a parliamentary bill designed to cut the rate of interest to an arbitrary 4%. Locke argued that people would find ways to circumvent the law, which would ultimately have unintended consequences. In a letter sent to a Member of Parliament entitled ‘Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising the Value of Money’ (1691), Locke wrote, “the Skilful, I say, will always so manage it, as to avoid the Prohibition of your Law, and keep out of its Penalty, do what you can. What then will be the unavoidable Consequences of such a Law?” He listed several, concerning the discouragement of lending and difficulty of borrowing, prejudice against widows and orphans with inheritance savings, increased advantage for specialist bankers and brokers, and sending money offshore.

Since then, there have been many examples of unintended consequences of government and industry targets in all sectors. A good case study of the experience of targets lies in British public services. This is not to say that other countries are different – targets in the public sector and business are prominent around the world, with the same effects now being recognised. But since the late 1990s, targets became a central feature of British government policy and thinking, and so it is a useful case study. Performance targets were created at senior levels of government, civil service and councils, and were cascaded down. It is sufficient for this article to look at some real examples from three sectors to see how targets can drive system behaviour. As you read on, consider how top-down targets feature in your own national and organisational culture.

Healthcare targets

|

| The targets helped to create a culture of fear and in doing so they resulted in gaming, falsification and bullying. Image: lydia_shiningbrightly CC BY 2.0 |

The disastrous consequences of a target culture in healthcare were tragically illustrated in the Mid-Staffordshire Hospital Trust scandal. It has been estimated, based on a 2009 Healthcare Commission investigation, that hundreds of patients may have died as a result of poor care between 2005 and 2008 at Stafford hospital.

A Public Inquiry report by Robert Francis QC was published on 6 February 2013. The report identified targets, culture and cost cutting as key themes in the failure of the system. According to the report, “This failure was in part the consequence of allowing a focus on reaching national access targets, achieving financial balance and seeking foundation trust status to be at the cost of delivering acceptable standards of care” (http://bit.ly/XVfeSa), The targets led to bullying, falsification of records, and poor quality care.

What stands out in the report is how targets affected behaviour at every level. This is best illustrated via the actual words of those who gave evidence. A whistleblower, Staff Nurse Donnelly, said, “Nurses were expected to break the rules as a matter of course in order to meet target, a prime example of this being the maximum four-hour wait time target for patients in A&E. Rather than “breach” the target, the length of waiting time would regularly be falsified on notes and computer records.”

According to Dr Turner, then a Specialist Registrar in emergency medicine (2002-2006), “The nurses were threatened on a near daily basis with losing their jobs if they did not get patients out within the 4 hours target … the nurses would move them when they got near to the 4 hours limit and place them in another part of the hospital … without people knowing and without receiving the medication.”

The pressure was not restricted to front-line staff. The Finance Director of South West Staffordshire Primary Care Trust, Susan Fisher, felt “intimidated…and was put under a lot of pressure to hit the targets.” Even Inspectors were “made to feel guilty if we are not achieving one inspection a week and all of the focus is on speed, targets and quantity,” according to Amanda Pollard, Specialist Inspector. She added, “The culture driven by the leadership of the CQC [Care Quality Commission] is target-driven in order to maintain reputation, but at the expense of quality”.

And consider the position of the Chief Executives. In the words of William Price, Chief Executive of South West Staffordshire Primary Care Trust, (2002-2006), “As Chief Executives we knew that targets were the priority and if we didn’t focus on them we would lose our jobs.” When a CEO is saying this, you know how much power those targets have.

Even the House of Commons agreed. A House of Commons Health Select Committee report on patient safety (June 2009, http://bit.ly/14YW07i) stated that. “…Government policy has too often given the impression that there are priorities, notably hitting targets (particularly for waiting lists, and Accident and Emergency waiting), achieving financial balance and achieving Foundation Trust status, which are more important than patient safety. This has undoubtedly, in a number of well documented cases, been a contributory factor in making services unsafe.”

With hindsight, everyone from the front-line to the government agreed: the targets were toxic. They were set at the top without a real understanding of how the system worked. They were disconnected from the staff and the end-users. But at the time, hardly anyone spoke up, else they faced accusations of incompetence or mental illness, physical threats from colleagues, and contractual gagging clauses. The targets helped to create a culture of fear and in doing so they resulted in gaming, falsification and bullying.

There are many other examples. Surgeons stated that they had to carry out more operations to hit targets under pressure from officials. In Scotland, there was a large increase in the practice of patients being marked ‘unavailable’ for treatment between 2008 and 2011, at a time when waiting time targets were being shortened. Around the UK, ambulance waiting time targets had unintended consequences, and were often not met anyway.

Police targets

|

| “The assessment regime creates a number of perverse incentives which draw resources away from local priorities.” Surrey Police Press Release. Image: Oscar in the middle CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 |

There were many unintended consequences. In one sex-crime squad, the Independent Police Complaints Commission found that officers pressured rape victims to drop claims to hit targets, and that the squad drew up its own policy to encourage victims to retract statements and boost the number of rapes classed as ‘no crime’, improving the squad’s poor detection rates threefold. Deborah Glass, the Commission’s deputy chair, said it was a "classic case of hitting the target but missing the point … The pressure to meet targets as a measure of success, rather than focussing on the outcome for the victim, resulted in the police losing sight of what policing is about.” (http://bit.ly/13kncMy).

In 2010, the British Home Secretary Theresa May told the Association of Chief Police Officers’ conference that she was getting rid of centrally driven statistical performance targets. She said: “Targets don’t fight crime. Targets hinder the fight against crime”. Superintendent Irene Curtis said that performance targets were rooted in the culture of policing “(This) has created a generation of people who are great at counting beans but don’t always recognise that doing the right thing is the best thing for the public.” (http://bit.ly/12QgP3k).

Even those police forces that hit their targets were not so happy. Surrey Police was assessed as one of the best forces in England and Wales by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and the Home Office via an analysis of Statutory Performance Indicators for 2006-7. But a press release by the Surrey Police in response to the good news stated that, “The assessment regime creates a number of perverse incentives which draw resources away from local priorities.” Chief Constable Bob Quick said, "The assessments were helpful a few years ago but the point of diminishing returns has long since passed. Some of the statutory targets skew activity away from the priorities the Surrey public have identified. We are at risk of claiming statistical success when real operational and resilience issues remain to be addressed.” (http://bit.ly/12QgP3k). The winners felt that leading a ‘league table’ built on targets did not equate to success.

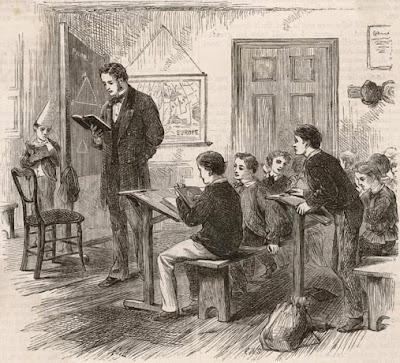

Education targets

|

| As one teacher put it, “I think that the targets culture is ruining education." Image: BES Photos CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 |

This latter target had a number of unintended consequences. Originally, the target did not specify which GCSE subjects were to be included, and so schools could claim success by including easier subjects, and not including English or Maths. As a result of this gaming, the target was revised in 2007 to include maths and English. But still it was then found that schools changed the way they worked to focus on pupils on the cusp of hitting Government targets – five C grades at GCSE. This meant that bright pupils tended to underachieve, while the target provided a perverse incentive to neglect those children with no chance of attaining five GCSE C grades.

Another form of gaming has involved entering students for two different tests for the same subject (GCSE and International GCSE). Reportedly, “Hundreds of state schools are entering pupils for two English GCSE-level qualifications at the same time in a bid to boost their grades…with only the better grade counting towards league tables” (http://bbc.in/Sj3Z6K). The government responded by drawing up reforms to league tables in a bid to reduce the focus on GCSE targets.

The targets on reducing truancy led to allegations of teachers manipulating attendance records by persuading parents of persistent absentees to sign forms saying they intended to educate their children at home. Overall, truancy targets were unsuccessful, and were abolished.

When asked what have been the consequences of targets and league tables in education, teachers have spoken out, saying that they promote shallow learning, teaching to the test, and gaming the system. As one teacher put it, “I think that the targets culture is ruining education. Teachers and senior staff are now more interested in doing whatever it takes (including cheating) to get their stats up than doing what is best for the students” (http://bit.ly/MAtkYp). The education targets are now under review.

The target fallacy

|

| Targets always have unintended consequences. Image: Paolo Camera CC BY 2.0 |

- Top-down. Targets are usually set from above, disconnected from the work. As such, they do not account for how the work really works.

- Arbitrary. Targets are usually arbitrary, with no reliable way to set them. They tend to focus on things that seem simple to measure, but are not necessarily meaningful.

- Sub-optimising. Targets focus on activities, functions and departments, but can sub-optimise the whole system. People may ensure that they meet their target, but harm the organisation as a whole, or allow other important but unmeasured aspects of performance to deteriorate.

- Resource-intensive. Targets create a burden of gathering, measuring and monitoring numbers that may be invalid.

- Demotivating. Targets can demotivate staff. Targets may be unrealistic, focus on the wrong things or provide no incentive to improve once the target is missed. What they often do motivate is the wrong sort of behaviour.

- Unintended consequences. Targets always have unintended consequences, such as cheating, gaming, blaming, and bullying. They make good people do the wrong things, especially if there are sanctions for not meeting the targets.

- Ineffective. Targets are often not met anyway, or else they become outdated, but are still chased.

How this is relevant for you – can you make a difference?

If you had patience to read up to here you are probably wondering how this could be relevant for an Air Traffic Controller or any other front-line operator in the aviation industry. Can you make a difference? Can you help prevent the kind of problems in aviation that we have seen in other industries? We think you can. Although targets may be cascaded down to you from your management and from regulatory authorities, you need to get involved. Reflect individually and collectively on how targets influence us and the system we work within. Talk with your colleagues and management – especially the supervisors who are the glue between senior management and operations – about targets in ATM, for instance:

- Do your targets echo the organisational goals?

- Are targets compatible with each other?

- Did you or your colleagues have a chance to advise in setting or reviewing your targets?

- Do targets reflect the real context of the daily operations?

- Do targets avoid putting pressure on staff?

- Are targets reviewed, modified, and removed to ensure they remain current?

If the answer to any of these question is ‘No’, then speak up – raise safety concerns, because this is relevant to your safety culture. Front line staff are not usually responsible for setting performance targets, but are the ones who are most affected.

Ultimately, we need to ensure that the possible unintended consequences of targets in ATM are understood by those who set and monitor targets. Remember that targets are supposed to be there to help us achieve our goals. And the primary goal of Air Traffic Management is to prevent collisions. Are targets helping us to achieve that goal?

Ultimately, we need to ensure that the possible unintended consequences of targets in ATM are understood by those who set and monitor targets. Remember that targets are supposed to be there to help us achieve our goals. And the primary goal of Air Traffic Management is to prevent collisions. Are targets helping us to achieve that goal?

Further reading

Meadows, D.H. (2008). Thinking in systems: A primer. Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

Meekings, A., Briault, S., Neely, A. (2011). How to avoid the problems of target-setting. Measuring Business Excellence, 15(3), 86 – 98. http://bit.ly/yeci8d

Seddon, J. (2003). Freedom from command and control: A better way to make the work work. Vanguard Consulting.

Seddon, J. (2008). Systems thinking in the public sector: The failure of the reform regime… and a manifesto for a better way. Triarchy Press.

Senge, P.M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization (Second edition). Random House.

Systems Thinking Review (2009). A systems perspective of targets. http://vimeo.com/58107852 (article and video).

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

Goats in sheep pens

When I was younger, my family had a smallholding with a few animals including chickens, ducks, geese, and few goats - one or two billies and several nannies. Thinking back to these goats made me think about what they can teach us about work in command-and-control organisations. The characteristics of goats, especially curiosity, independence and foraging behaviour, highlight to me how command and control organisations need goat thinkers - constructive rebels including systems thinkers, design thinkers, and humanistic thinkers - to survive.

The first thing you notice about actual goats is that they are curious and inquisitive by nature. They will tend to find, do and reach things that you don't expect. They are not very good at being penned in - they will test their enclosure for gaps or weaknesses. Once found, they will remember and use such gaps. I remember coming home to find that the vegetation in the goat enclosure was not to their liking, and so they would squeeze her head through the fence to get richer material on the outside. If you enter a goat enclosure, they are quite likely to come to you. Sheep, by contrast, are cautious but indifferent creatures - more wary but less interested.

Goats are independent animals, happy to go their own way as well as with other goats. They don't follow for the sake of following, but rather for the sake of curiosity. Sheep are very much herd animals, conforming with the flock and obedient to the shepherd.

In their diet and foraging behaviour, goats are browsers and will taste nearly anything, but they have a varied and nutritious diet - leaves, twigs, vines, and shrubs, as well grass. Goats are flexible and agile creatures and will forage in hard to reach places. Sheep are grazers and tend to prefer short, tender grass, clover and other easy-to-munch stuff. If you want a nice neat lawn, sheep are what you need. But goats will pull out the weeds and aerate the soil while they are at it.

In safety-related or other command and control organisations, goat thinkers are not hard to spot. They are usually the ones who expose gaps and unearth opportunities. You will find goat thinkers foraging on a wide variety of material from different fields - more complex, interrelated and challenging. Goat thinkers naturally think outside the pen and so will see beyond artificial boundaries. Goat thinkers need to find out more about what they don't know - forever a learner - not more about what they already know. They are led by the shepherd of curiosity - constantly finding out more about developing situations, asking difficult questions of themselves and others, admitting and embracing uncertainty, challenging assumptions, decisions, mindsets, and authority. Goat thinkers are the seekers, the questioners, the non-conformers, the innovators and - in some cases - the whistleblowers.

When the work landscape embraces goat thinking, goat thinkers can achieve remarkable results. But usually this is not the case, so goat thinkers need to navigate the territory carefully. Along the journey, there are a few pitfalls, and ways to avoid them:

The first thing you notice about actual goats is that they are curious and inquisitive by nature. They will tend to find, do and reach things that you don't expect. They are not very good at being penned in - they will test their enclosure for gaps or weaknesses. Once found, they will remember and use such gaps. I remember coming home to find that the vegetation in the goat enclosure was not to their liking, and so they would squeeze her head through the fence to get richer material on the outside. If you enter a goat enclosure, they are quite likely to come to you. Sheep, by contrast, are cautious but indifferent creatures - more wary but less interested.

Goats are independent animals, happy to go their own way as well as with other goats. They don't follow for the sake of following, but rather for the sake of curiosity. Sheep are very much herd animals, conforming with the flock and obedient to the shepherd.

In their diet and foraging behaviour, goats are browsers and will taste nearly anything, but they have a varied and nutritious diet - leaves, twigs, vines, and shrubs, as well grass. Goats are flexible and agile creatures and will forage in hard to reach places. Sheep are grazers and tend to prefer short, tender grass, clover and other easy-to-munch stuff. If you want a nice neat lawn, sheep are what you need. But goats will pull out the weeds and aerate the soil while they are at it.

In safety-related or other command and control organisations, goat thinkers are not hard to spot. They are usually the ones who expose gaps and unearth opportunities. You will find goat thinkers foraging on a wide variety of material from different fields - more complex, interrelated and challenging. Goat thinkers naturally think outside the pen and so will see beyond artificial boundaries. Goat thinkers need to find out more about what they don't know - forever a learner - not more about what they already know. They are led by the shepherd of curiosity - constantly finding out more about developing situations, asking difficult questions of themselves and others, admitting and embracing uncertainty, challenging assumptions, decisions, mindsets, and authority. Goat thinkers are the seekers, the questioners, the non-conformers, the innovators and - in some cases - the whistleblowers.

When the work landscape embraces goat thinking, goat thinkers can achieve remarkable results. But usually this is not the case, so goat thinkers need to navigate the territory carefully. Along the journey, there are a few pitfalls, and ways to avoid them:

- Mental conflict: Once you know something, you cannot unknow it. New thinking plus old methods naturally leads to cognitive dissonance. Gradual introduction of new thinking may be necessary - pragmatism and proven small wins set the ground for more radical change. But keep the faith.

- Frustration: Goat thinkers in a command and control organisation can be frustrated as new perspectives are resisted. Finding the right levers for change is important. Working on the wrong levers, such as died-in-the-wool sheep and die-hard refuseniks, is a waste of time and energy. Patience and constancy of purpose are key.

- Isolation: Without the mentality and protection of a herd, it may be a lonely and less secure life for the goat thinker. Goat thinkers do not naturally flock, and getting agreement can take time. To overcome isolation, a collective of goat thinkers is crucial. They don't have to live in the same pen - and might not want to.

- Ostracism: The frustrated goat thinker, who refuses to share the food, can't get on with others, and perhaps lowers horns too early, may well be ignored or kept on a leash. (We had a real big billy goat like this!) Prevention is better than cure: be patient, there's (usually) no need to make enemies; collaborate and involve.

- Immobilisation: By sticking their neck out of the fence, goat thinkers can get stuck. (Goats really do this. The horns act as a sort of expanding wall plug/screw anchor between fence posts.) Once you have declared the failure of a paradigm, system or process, you are expected to have a solution ready (even though this is neither logical nor fair). Having a next step in hand - needing collaboration - lends credibility.

- Ethical dilemmas: Goat thinkers may face moral or ethical dilemmas. They need a good compass, and courage. Speaking up is easy if everyone does it, but mostly they don't. Mostly, it's down to the goat thinkers.

- Rejection: Once goat thinkers lower their horns to take on a fight, they have to follow through, and may well be ejected from the pen. Witness the fate of many whistleblowers...

Thursday, May 23, 2013

If you want to understand risk, you need to get out from behind your desk

I saw this poster in an airport some time ago. It is an advert for an insurance company and shows a person in a helicopter with a note, "One thing, if you want to understand risk, you need to get out from behind your desk".

How connected are safety specialists with operational staff and the operational environment, where the day-to-day safety is created, to understand the operational world? How much of our time is spent behind a desk or in meetings? In every industry, there is a danger that those working at the blunt-end (in any role) become detached from those in the sharp-end of operations.

Some years ago, I was part of a major project involving a change to a new facility along with several other changes. I entered the project at a relatively late pre-operational stage - everything was designed, built and mostly installed. The operators were training for the change. The risk assessments, including human factors, had already been done and were exhaustive, comprising hundreds of pages of documentation from workshops and analysis. After reading some of this material, I could not get a real sense for what was going on. The only way I could see to understand the change was to to enter simulator training for a week and just watch and listen.

I was shocked at what I experienced. What I saw was that the operational staff were not ready for the move, despite what management and various specialists believed. Being with them, watching them and listening to them allowed for a moment-by-moment empathy of the operators' experiences (process empathy) and a near understanding of their worlds (person empathy). The operators could use the equipment, but they could not do the rest of the job safely at the same time. Some lost the picture, unable to continue. Some broke down crying. Operational staff had already spoken up, but the message wasn't getting through.

Nothing in any analysis could give anything like this understanding, because it was just that - analysis; work-as-imagined, decontextualised, decomposed and detached from the reality of work-as-done.

As I arrived home after the fourth day in the simulator, all I felt I could do, as a safety specialist was write honestly and openly about what I saw. So I wrote a letter in the late hours of the night. The next day, I went in to the facility to try to talk to someone about what I had seen, as a newcomer and outsider to the project since the Monday. When I arrived, I read the letter to the project and facility safety manager. Then I read it again, with the safety managers, to a senior manager, then again to the facility manager and several senior project and facility staff in an impromptu meeting. While there was some resistance, most listened and understood, and agreed to look into it further.

But there was some resistance to this unorthodox approach and, quite rightly, I was challenged. I could only think of one question in reply: "Have you been into the simulator recently?" What was most surprising to me at the time was that none of the (non-operational) managers or specialists present at the impromptu meeting had spent time in the simulator during training. There are many reasons why sitting in a simulator with operational staff does not seem like a priority on a large project, but among them are safety regulations and safety management systems. The need to comply with such requirements may seem like a very good reason not to bother getting involved with operational issues. Ironically, both can take the focus away from the sharp-end of safety. Because time and other resources are always limited, there has to be a trade-off. The trade-off often favours safety-as-imagined, as opposed to safety-as-done.

In the weeks following, it was decided to delay the opening of the new facility to allow for more experience in the simulator and the new facility. During this time, two or three big human factors issues (including a significant risk associated with display design) were identified from informal discussions and observations. These issues were resolved during these months. The facility opened successfully a few months later.

Before this experience, I had spent most of my time in this organisation behind a desk, with little access to operational environments or staff. From that position I could identify risks, but could not really understand risk.

The message in the insurance poster reminded me of this experience and has been a sort of mantra ever since:

How connected are safety specialists with operational staff and the operational environment, where the day-to-day safety is created, to understand the operational world? How much of our time is spent behind a desk or in meetings? In every industry, there is a danger that those working at the blunt-end (in any role) become detached from those in the sharp-end of operations.

Some years ago, I was part of a major project involving a change to a new facility along with several other changes. I entered the project at a relatively late pre-operational stage - everything was designed, built and mostly installed. The operators were training for the change. The risk assessments, including human factors, had already been done and were exhaustive, comprising hundreds of pages of documentation from workshops and analysis. After reading some of this material, I could not get a real sense for what was going on. The only way I could see to understand the change was to to enter simulator training for a week and just watch and listen.

I was shocked at what I experienced. What I saw was that the operational staff were not ready for the move, despite what management and various specialists believed. Being with them, watching them and listening to them allowed for a moment-by-moment empathy of the operators' experiences (process empathy) and a near understanding of their worlds (person empathy). The operators could use the equipment, but they could not do the rest of the job safely at the same time. Some lost the picture, unable to continue. Some broke down crying. Operational staff had already spoken up, but the message wasn't getting through.

Nothing in any analysis could give anything like this understanding, because it was just that - analysis; work-as-imagined, decontextualised, decomposed and detached from the reality of work-as-done.

As I arrived home after the fourth day in the simulator, all I felt I could do, as a safety specialist was write honestly and openly about what I saw. So I wrote a letter in the late hours of the night. The next day, I went in to the facility to try to talk to someone about what I had seen, as a newcomer and outsider to the project since the Monday. When I arrived, I read the letter to the project and facility safety manager. Then I read it again, with the safety managers, to a senior manager, then again to the facility manager and several senior project and facility staff in an impromptu meeting. While there was some resistance, most listened and understood, and agreed to look into it further.

But there was some resistance to this unorthodox approach and, quite rightly, I was challenged. I could only think of one question in reply: "Have you been into the simulator recently?" What was most surprising to me at the time was that none of the (non-operational) managers or specialists present at the impromptu meeting had spent time in the simulator during training. There are many reasons why sitting in a simulator with operational staff does not seem like a priority on a large project, but among them are safety regulations and safety management systems. The need to comply with such requirements may seem like a very good reason not to bother getting involved with operational issues. Ironically, both can take the focus away from the sharp-end of safety. Because time and other resources are always limited, there has to be a trade-off. The trade-off often favours safety-as-imagined, as opposed to safety-as-done.

In the weeks following, it was decided to delay the opening of the new facility to allow for more experience in the simulator and the new facility. During this time, two or three big human factors issues (including a significant risk associated with display design) were identified from informal discussions and observations. These issues were resolved during these months. The facility opened successfully a few months later.

Before this experience, I had spent most of my time in this organisation behind a desk, with little access to operational environments or staff. From that position I could identify risks, but could not really understand risk.

The message in the insurance poster reminded me of this experience and has been a sort of mantra ever since:

If you want to understand risk, you need to get out from behind your desk.

Friday, April 12, 2013

Why do we resist new thinking about safety and systems?

Something I have been thinking about for a while is the way that we look at safety and systems - the unstated assumptions and core beliefs. The paradigm and the related shared ideas about safety are little different now to what they were 20 or 30 years ago. New thinking struggles to take root. We continue to explain adverse events in complex systems as 'human error'. We continue to blame people for making 'errors', even when the person is balancing conflicting goals under production pressure (such as this case). We continue to try to understand safety by studying very small numbers of adverse events (tokens of unsafety), without trying to understand how we manage to succeed under varying conditions (safety). It is a bit like trying to understand happiness by focusing only on rare episodes of misery. It doesn't really make sense. We are left with what Erik Hollnagel calls 'Safety I' thinking as well as what Sidney Dekker calls 'old view' thinking. The paradigm has a firm hold on our mindsets - our self-reinforcing beliefs. The paradigm is our mindset.

Why are we so resistant to change? Over at Safety Differently, Sidney Dekker recently posted a blog called 'Can safety renew itself?', which resonates with my recent thinking. Dekker asks "Is the safety profession uniquely incapable of renewing itself?" He makes the case that the safety profession is inherently conservative and risk averse. But these qualities stifle innovation, which naturally requires questioning the assumptions that underlie our practices, and taking risks.

It is something that I can't help but notice. When it comes to safety and systems, we seem much more comfortable dismissing new thinking than even challenging old thinking. Our skepticism is reserved for the new, while the old is accepted as 'time-served'. So we are left with old ideas and old models in a state of safety stagnancy. Our most widely accepted models of accident causation are still simple linear models. Non-linear safety models are dismissed as 'too complicted', or 'unproven'. There is not the same determination to question whether assumptions about linear cause-effect relationships really exist in complex systems. The 'new view', which sees human error as a symptom, not a cause, is often seen as just excuses. But we are less willing to think about whether human error is a viable 'cause'. We are even less willing to question whether 'human error' is even a useful concept, in a complex, underspecified system where people have to make constant adjustments and trade-offs - and failures are emergent. The concept of 'performance variability' is seen by some as wishy washy. But the good outcomes that arise from it are not considered further. Proposals to reconsider attempts to quantify human reliability in complex systems are dismissed. But there is not the same urge to critique the realism of the source data and the sense behind the formulae that underlie 'current' (i.e. 1980s) human reliability assessment (HRA) techniques. There are plenty of reviews of HRA, but they rarely seem to question the basic assumptions of the approach or its techniques.

Why is this? Dekker draws a parallel with the argument of Enlightenment thinker Immanuel Kant, regarding self-incurred tutelage as a mental self-defence against new thinking.

"Tutelage is the incapacity to use our own understanding without the guidance of someone else or some institution... Tutelage means relinquishing your own brainpower and conform so as to keep the peace, keep a job. But you also help keep bad ideas in place, keep dying strategies alive."

|

| Little Johnny came to regret asking awkward questions about Heinrich's pyramid. |

Personal Barriers

I have almost certainly fallen prey to nearly all of these at some point, and so speak I from experience as well as observation. If new thinking strikes any of these nerves, I try to listen - hard as it may be.- LACK OF KNOWLEDGE. This is the most basic personal barrier, and seems to be all too common. Lack of knowledge is not usually through a lack of ability or intellect, but a lack of time or inclination. For whatever reason, many safety practitioners do not seem to read much about safety theory. The word theory even seems to have a bad name, and yet it should be the basis for practice, otherwise our science and practice is populist, or even puerile, rather than pragmatic (this drift is evident also in psychology and other disciplines). Some reading and listening is needed to challenge one's own assumptions. Hearing something new can be challenging because it is new. For me personally, several system safety thinkers and systems thinkers have kept me challenging my own assumptions over the years.

- FEAR. Fear is the reason most closely related to Kant's, as cited by Dekker. Erik Hollnagel has cited the fear of uncertainty referred to by Nietzsche in 'Twilight of the Idols, or, How to Philosophize with a Hammer': "First principle: any explanation is better than none. Because it is fundamentally just our desire to be rid of an unpleasant uncertainty, we are not very particular about how we get rid of it: the first interpretation that explains the unknown in familiar terms feels so good that one "accepts it as true."" What old thinking in safety does, is provide an quick explanation that fits our mental model. A look at the reporting of accidents in the media nearly always turns up a very simple explanation: human error. More specifically for safety practitioners, when you have invested decades in a profession, there can be little more threatening than to consider that your mindset or (at least some of) your fundamental assumptions or beliefs may be faulty. If you are an 'expert' in something that you think is particularly important (such as root cause analysis or behavioural safety), it is threatening to be demoted to an expert in something that may not be so valid after all. Rethinking one's assumptions can create a cognitive dissonance, and may have financial consequences.

- PRIDE. If you are an 'expert', then there is not much room left to be a learner, or to innovate. Being a learner means not 'knowing', and instead being curious and challenging one's own assumptions. It means experimenting, taking risks and making mistakes. Notice how children learn? When left to their own devices, they do all of these things. Let's quit being experts (we never were anyway). Only by learning to be a learner can we ever hope to understand systems.

- HABIT. It seems to me that our mindsets about safety and systems are self-reinforced not only by beliefs, but by habits of thought, language and method. We habitually think in terms of bad apples or root causes, and linear cause-effect relationships. We habitually talk about "human error", "violation", "fault", "failure", etc - it is ingrained in our safety vocabulary. We habitually use the old methods that we know so well. It is a routine, and a kind of mental laziness. To make new roads, we need to step off these well-trodden mental paths.

- CONFORMITY. Most people naturally want to conform. We learn this from a young age, and it is imprinted via schooling. As Dekker mentions, you want to fit in with your colleagues, boss, and clients to keep the peace and keep a job. But fitting in and avoiding conflict is not how ideas evolve. Ideas evolve by standing out.

- OBEDIENCE. In some environments, you have to think a certain way to get by. It is not just fitting it, it is being told to, and having to - if you are to survive there. This is especially the case in command and control cultures and highly regulated industries where uniformity is enforced. If you work for a company which specialises in safety via the old paradigm, you have little choice - to obey or leave.

System Barriers

As pointed out by Donnella Meadows in 'Thinking in Systems', "Paradigms are the sources of systems". Barriers to new thinking about safety are built into the very structures of the organisations and systems that we work within, with and for, and so are the most powerful. These barriers breed and interact with the personal barriers, setting up multiple interconnected feedback loops that reinforce the paradigm itself.- GOALS. Goals are one of the most important parts of any system because they represent the purpose of the system and set the direction for the system. They also reinforce the paradigm out of which the system arises. Safety goals are typically expressed in terms of unsafety, and so are the quantification of these goals, relating to accidents and injuries, such as target levels of safety or safety target values. Some organisations even have targets regarding errors. Such goals stifle thinking and reinforce the existing mindset.

- DEMAND. Market forces and regulation can be powerful suppressor of new safety thinking. Not knowing any different, and forced by regulation, internal and external clients demand work that rests on old thinking. The paradigm, and often the approach, is often specified in calls for tender. Old thinking is a steady cash cow.

- RULES & INCENTIVES. Rules regarding safety emerge from and reinforce the existing paradigm of safety. Rules limit and constrain safety thinking, and the products of thinking. Examples include regulations, standards and management systems with designed-in old thinking. Within the systems in which we work are various incentives - contracts, funding, prizes, bonuses, and publications - as well as punishments, that reinforce the paradigm.

- MEASURES. What is measured in safety has a great influence on the mindset about safety. A reading of Deming reveals that if you use a different measure, you get a different result. We typically measure adverse events and other tokens of unsafety as the only measures of safety. What we need is measures of safety - of the system's ability to adapt, reorganise and succeeed under varying conditions.

- METHODS. Changing the paradigm inevitably means changing some methods. Most existing methods (especially analytical techniques), as well as databases, are based on old paradigm thinking. A common challenge to new thinking is that there is a lack of techniques. There is a general expectation that the techniques should just be there. For corporations, changing methods costs, especially those that are computerised and those that are used for comparing over time.

- EDUCATION. Training and education at post-graduate level (which is typically where safety concepts are encountered) are influenced heavily by demand. And demand is still to be rooted in old paradigms and models. Reflecting new thinking in safety courses either means not meeting demand or creating a conflict of paradigms within the course. This is not fun for an educator.

Can the paradigm be changed directly? Donella Meadows seems to thinks it can.

"Thomas Kuhn, who wrote the seminal book about the great paradigm shifts of science, has a lot to say about that. You keep pointing at the anomalies and failures in the old paradigm. You keep speaking and acting, loudly and with assurance, from the new one. You insert people with the new paradigm in places of public visibility and power. You don’t waste time with reactionaries; rather, you work with active change agents and with the vast middle ground of people who are open-minded." (p. 164).

Changing the safety paradigm is a slow process, but one that is possible, and has happened many times over in most disciplines. But it will take a bold step to pull the system levers, and this step - more than anything - needs courage.

Sunday, March 17, 2013

John Locke and the unintended consequences of targets

With the huge evidence of the destructive effect of targets in complex systems such as healthcare, policing, and education, I wondered: 1) how recent is this problem, and 2) when did we first become aware of how top-down, arbitrary numerical targets distort and suboptimise systems, leading people to cheat, game, fiddle and manipulate the system in order to meet or get around the target. When I say "when did we first become aware", I am not implying that we are generally aware of their toxic effects now - targets still seem to be taken for granted, and even when their effects become clear, people argue either they were the wrong targets, or that there were too many or not enough, and stick with the target concept as they don't know what else to do.

While the UK's mass experiment with top-down, arbitrary targets in public services began in the 1990s, some bright spark worked out the pitfalls of this kind of thinking over 300 years earlier; English philosopher John Locke - one of the most influential Enlightenment Thinkers (and seemingly a System Thinker).

In 1668-1669, the House of Lords' committee held hearings on a Bill to lower interest

to an arbitrary fixed rate of 4%. The House heard testimony from members of the King's Council of Trade, and the English merchant and politician Josiah Child had a position on this Council. Child was an proponent of mercantilism, a

protectionist economic doctrine involving heavy regulation and colonial

expansion. The idea of the (sort of) target was to benchmark with cashed-up Holland (oh, you thought benchmarking started with Xerox?), but Child treated the maximum rate of interest as the cure for many economic and social ills. Another member of the Council of Trade, and also a member of the Lords' committee, was Lord Ashley. Ashley opposed the Bill and enlisted Locke's help via an as-yet-unpublished manuscript, Some of the Consequences that are like to follow upon Lessening of Interest to Four Percent (1668).

Locke urged the defeat of the target, which was enshrined in the Bill. Being a canny Systems Thinker, he argued

that the law would distort the economic system and people would find ways to circumvent it; the target would

ultimately have unintended consequences and leave the economy and nation worse off. It seemed to work; the target was killed off in 1669. But in the early 1690’s, Child still wanted to arbitrarily lower interest rates, and the London merchants supported him.

When Bills were introduced in 1691, Locke revised his 1668 memorandum and published it as Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising the Value of Money (1691). Locke warned that,

It is worth reading at least some of his 'letter', in its delightful Early Modern English, but note that Locke lived a few years before twitter. Unhindered by a 140 character restriction, Locke went for a 45,000 word argument. But it worked. The 4 percent target was killed again in the House of Lords.

Over 300 years later, we seem unable to grasp that arbitrary, top-down targets always have unintended consequences, which are often worse than the possible intended consequences.

While the UK's mass experiment with top-down, arbitrary targets in public services began in the 1990s, some bright spark worked out the pitfalls of this kind of thinking over 300 years earlier; English philosopher John Locke - one of the most influential Enlightenment Thinkers (and seemingly a System Thinker).

|

| John Locke (1632-1704): Enlightened Systems Thinker |

|

| Josiah Child 1630-1699: Command and Control Thinker |

“the Skilful, I say, will always so manage it, as to avoid the Prohibition of your Law, and keep out of its Penalty, do what you can. What then will be the unavoidable Consequences of such a Law?”Locke had a fair idea about these unintended consequences. He listed several, concerning the discouragement of lending and difficulty of borrowing, prejudice against widows and orphans with inheritance savings, increased advantage for specialist bankers, brokers and merchants, money hived offshore, and perjury:

"1. It will make the Difficulty of Borrowing and Lending much greater; whereby Trade (the Foundation of Riches) will be obstructed.

2. It will be a Prejudice to none but those who most need Assistance and Help, I mean Widows and Orphans, and others uninstructed in the Arts and Managements of more skilful Men; whose Estates lying in Money, they will be sure, especially Orphans, to have no more Profit of their Money, than what Interest the Law barely allows.

3. It will mightily encrease the Advantage of Bankers and Scriveners, and other such expert Brokers: Who skilled in the Arts ofputting out Money according to the true and natural Value, which the present State of Trade, Money and Debts, shall always raise Interest to, they will infallibly get, what the true Value of Interest shall be, above the Legal. For Men finding the Convenience of Lodging their Money in Hands, where they can be sure of it at short Warning, the Ignorant and Lazy will be forwardest to put it into these Mens hands, who are known willingly to receive it, and where they can readily have the whole, or a part, upon any sudden Occasion, that may call for it.

4. I fear I may reckon it as one of the probable Consequences of such a Law, That it is likely to cause great Perjury in the Nation; a Crime, than which nothing is more carefully to be prevented by Lawmakers, not only by Penalties, that shall attend apparent and proved Perjury; but by avoiding and lessening, as much as may be, the Temptations to it. For where those are strong, (as they are where Men shall Swear for their own Advantage) there the fear of Penalties to follow will have little Restraint; especially if the Crime be hard to be proved. All which I suppose will happen in this Case, where ways will be found out to receive Money upon other Pretences than for Use, to evade the Rule and Rigour of the Law: And there will be secret Trusts and Collusions amongst Men, that though they may be suspected, can never be proved without their own Confession."Locke knew that top-down, arbitrary numerical targets distort and suboptimise systems, and lead people to cheat, game, fiddle and manipulate the system in order to meet or get around the target. Is this ringing any bells?

It is worth reading at least some of his 'letter', in its delightful Early Modern English, but note that Locke lived a few years before twitter. Unhindered by a 140 character restriction, Locke went for a 45,000 word argument. But it worked. The 4 percent target was killed again in the House of Lords.

Over 300 years later, we seem unable to grasp that arbitrary, top-down targets always have unintended consequences, which are often worse than the possible intended consequences.

Thursday, February 7, 2013

"So you have an under-reporting problem?" System barriers to incident reporting.

The reporting of safety occurrences and safety-relevant issues and conditions is an essential activity in a learning organisation. Unless people speak up, be it concerns about unreliable equipment, unworkable procedures, or any human performance issue, trouble will fester in the system. In my experience in safety investigation, safety culture and human factors across industries, one of the clearest signs of trouble in a safety-related organisation is a reluctance among staff to report safety issues.

Non-reporting can be hard to detect, especially when managers are disconnected from the work. There may be a built-in motivation not to be curious about a lack of reports: under-reporting gives the illusion that an organisation has few incidents or safety problems, and this may give a reassurance of safety (while a preoccupation with failure, or 'chronic unease', might be true for those who have worked in high reliability organisations). Where it is discovered that relevant events or issues are not being reported, too often this is seen as a sign of a person, or team, gone bad - ignorant, lazy or irresponsible. This might be the case, but only if ten or so other issues have been discounted. I have tried to distill these below, along with some relevant Safety Culture Discussion Cards.

"So you have an under-reporting problem?" Questions for the curious.

1. Is the purpose of reporting understood, and is it consistent with the purpose of the work and organisation?

2. Are people trated fairly (and not blamed or published) when reporting?

3. Are there no incentives to under-report?

4. Do people know how to report, have good access to a usable reporting method?

5. Are people given sufficient time to make the report?

6. Do people have appropriate privacy and confidentiality when reporting?

7. Are the issues or occurrences investigated by independent, competent, respected individuals?

8. Are reporters actively involved and informed at every stage of the investigation?

9. Does anything improve as a result of investigations, and are the changes communicated properly?

10. Is there a local culture of reporting, where reporting is the norm and encouraged by colleagues and supervisors?

If your organisation has a problem with under-reporting, the chances are there are a few No's and Don't Know's in the answers to the above. In nearly all cases, under-reporting is a system problem. If you're not sure, and want to find out, ask those who could report about the what gets in the way of reporting (for other people, of course). The Safety Culture Discussion Cards might help.

Non-reporting can be hard to detect, especially when managers are disconnected from the work. There may be a built-in motivation not to be curious about a lack of reports: under-reporting gives the illusion that an organisation has few incidents or safety problems, and this may give a reassurance of safety (while a preoccupation with failure, or 'chronic unease', might be true for those who have worked in high reliability organisations). Where it is discovered that relevant events or issues are not being reported, too often this is seen as a sign of a person, or team, gone bad - ignorant, lazy or irresponsible. This might be the case, but only if ten or so other issues have been discounted. I have tried to distill these below, along with some relevant Safety Culture Discussion Cards.

"So you have an under-reporting problem?" Questions for the curious.

1. Is the purpose of reporting understood, and is it consistent with the purpose of the work and organisation?

Yes / No / Don't Know

This is the first and most fundamental thing. As Donella Meadows noted in her book Thinking in Systems, "The least obvious part of the system, its function or purpose, is often the most crucial determinant of the system's behaviour". The purpose of reporting may be completely unknown, vague, ambiguous, or (most likely) seemingly inconsistent with the work or with the purpose of at least part of organisation (e.g. a department or division), and its related goals. The purpose of reporting may relate primarily to monitoring and compliance with rules, regulations, standards or procedures. The purpose may relate to checking against organisational goals and numerical targets (e.g. relating to equipment failures, 'errors', safety outcomes, etc). In both cases, there is probably little perceived value to the reporter (and may be little value to the organisation) and incompatible purposes, and hence a disincentive to report. From a more useful viewpoint, the purpose of reporting may be viewed in terms of learning and improving how the work works. Things like demands, goal conflicts, performance variability and capability, flow and conditions become the things of interest. In other words, the purpose of reporting should be compatible with the purpose of the work itself. See Card 1c, Card 1g and Card 4c.2. Are people trated fairly (and not blamed or published) when reporting?

Yes / No / Don't Know

An unjust culture is probably the most powerful reason not to report. If people are blamed or punished for their good-will performance, others will not want to report. The effect has a long shelf-life; these particular stories live on in the organisation, serving as disincentives long after the incident. Punishment may take several froms: inquisitorial investigation interview, 'explain yourself' meeting with the boss, formal warning, public admonishment and shaming, non-renewal of contract, loss of job, prosecution...even vigilante revenge attack. A culture of fear may be cultivated by designed organisational processes. The independent Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) estimated that up to 600 RIDDOR incidents were not reported between 2005 and 2010

due to pressure from Network Rail. One key reason was that contractors were under pressure to meet accident targets - a clear disincentive to report, built into the system. The fears of staff were reasonable and took various forms similar to those listed above. In the case of possible punishment by external organisations, a question mark arises over internal support by the organisation. In these cases, if the organisation is not supportive (legally and emotionally), there is motivation not to report. See Card 3h, Card 3d and Card 3g and Card 3f.3. Are there no incentives to under-report?

Yes / No / Don't Know

Messages from organisations that accidents, incidents, hazards, etc., 'must be reported' are cancelled out immediately by institutional perverse incentives not to report. They are often linked to targets of various kinds (either clearly related to safety or not), league tables which count safety occurrences, bonuses, prizes, etc. Many incentives combine reward and punishment and so are devastatingly effective in preventing reporting. The US OSHA notes in a recent whistleblower memo regarding safety incentive and disincentive policies and practices

that, "some employers establish programs that unintentionally or

intentionally provide employees an incentive to not report injuries". Perverse incentives were identified by RSSB in Network Rail's (at least as it operated then) Safety 365 Challenge, in which "staff and departments were rewarded for

having an accident-free year with gifts of certificates and branded

fleeces and mugs. But failure to get a certificate could lead to staff and departments being downgraded..." (as reported here). Anson Jack, the RSSB's

director of risk, noted that the initiatives together

with the culture at Network Rail led to unintended consequences of

under-reporting. See Card 1f and Card 4h.4. Do people know how to report, have good access to a usable reporting method?

Yes / No / Don't Know

It is easy to assume that people have the relevant information and instruction on how to report, but especially with a complicated reporting system or form, it's worth asking whether people really understand how to report. Complicated forms and unusable systems are off-putting, as is asking for help from colleagues or a supervisors (especially in a stressed environment). Even when people know how to report, if the reporting system is hard to access or requires excessive or seemingly irrelevant input, then you have accessibility and usability barriers in the system. See Card 3j.5. Are people given sufficient time to make the report?

Yes / No / Don't Know

Reporting incidents and safety issues needs time to think and time to write. Ideally, the report allows the person to tell the story of what happened, not just tick some boxes, and allows then to reflect on the system influences. The time provided for the activity will send a message to the person about how important it is. If people have to report in their breaks from operational duty or after hours, then under-reporting has to be expected. See Card 2h.6. Do people have appropriate privacy and confidentiality when reporting?

Yes / No / Don't Know

Reporting safety related issues and events can be sensitive in many ways. The issue may be serious, with possible further consequences or may cause some embarrassment, awkwardness or ill-feeling. If people have to go to their manager's office or to a public PC in the café, expect them to be put off. Beyond privacy, confidentiality is crucial. Incident reporting programmes that have switched to confidential reporting programmes have seen significant increases in reports, and not just because of a reduction in fear of retribution. As Dekker & Laursen (2007) reported, with non-confidential, punitive reporting systems, people may actually be very willing to report - at a very superficial level, focusing on the first story ('human error') not the second story (systemic vulnerabilities). Even with confidential systems, the first question that comes to mind for some is not about what, how or why, but rather who. Even confidential reporting systems often require identifying details (such as a name, or else date, time, shift, location, etc), which might be used to try to identify the reporter. Confidentiality shouldn't be an issue in a culture which is fair, open and values learning, but it seems to remain key to encouraging reporting. See Card 3l and Card 3f. 7. Are the issues or occurrences investigated by independent, competent, respected individuals?

Yes / No / Don't Know

If the investigator is not independent (and is instead subject to interference), if he or she lacks training and competency in investigation, or is simply not respected, then under-reporting will occur. The location of the investigation function within the organisation will be relevant; independence must be in reality, not just on an organisation chart and in a safety management manual. Ideally, investigators would be carefully selected and would have chosen the role, rather than being forced to do it. Once they are in the role, training in human factors and organisational factors is useful, but even more useful is a systems thinking and humanistic approach, with values including empathy, respect and genuineness. See Card 3n and Card 2a.8. Are reporters actively involved and informed at every stage of the investigation?

Yes / No / Don't Know

The best investigations, in my experience, involve reportees (and others involved) properly in the investigation. The reporter, despite sharing the same memory and cognitive biases as all of us (including investigators), is essential to tell their story, make sense of the issues, and think about possible fixes. How those involved understand the event (including different and seemingly incompatible versions of accounts, which will naturally arise from different perspectives) gives valuable information. Whether those involved are seen as co-investigators or subjects will affect the result and the likelihood of reporting. During and after the investigation, a lack of feedback is probably the most common system problem; often the result of flaws in the safety management system or an under-resourced investigation team. More generally, people need to see the results of investigations in order to trust them.

Not providing access to reports may confirm fears about reporting. On the

other end of the scale, overwhelming people with batches of reports and forcing

them to read lengthy and sometimes irrelevant reports will not help.

See Card 3k, Card 3m and Card 8a.9. Does anything improve as a result of investigations, and are the changes communicated properly?

Yes / No / Don't Know

The vast majority of organisational troubles and opportunities for improvement are due to the design of the system (94% if you accept Demming's estimate, p. 315), not the individual performance of the workers. If occurrence reports lead to no systemic changes, it seems nearly pointless to report. Often, individuals have reported the same issue before, to no effect. This teaches them that reporting is pointless, going back to Question 1. Even if system changes are made following reports, not communicating to the wider population, via communication channels that they use, means that people may not know they changes have happened, or that they resulted from reporting. See Card 3i, Card 3c, Card 6d and Card 6h. 10. Is there a local culture of reporting, where reporting is the norm and encouraged by colleagues and supervisors?

Yes / No / Don't Know

People naturally want to fit in. If colleagues and supervisors discourage reporting, as is sometimes the case, then individuals will be uncomfortable, and will have to balance feelings of responsibility against a need to get along with colleagues. The answer to this last question will nearly always be dependent on the answers to the previous questions, though. See Card 3a and Card 3o.If your organisation has a problem with under-reporting, the chances are there are a few No's and Don't Know's in the answers to the above. In nearly all cases, under-reporting is a system problem. If you're not sure, and want to find out, ask those who could report about the what gets in the way of reporting (for other people, of course). The Safety Culture Discussion Cards might help.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)